Senior Lecturer in Philosophy

Director of the Civic Knowledge Project

Chicago Uiversity (USA)

Placido the Sidgwickian—Remembering Placido Bucolo

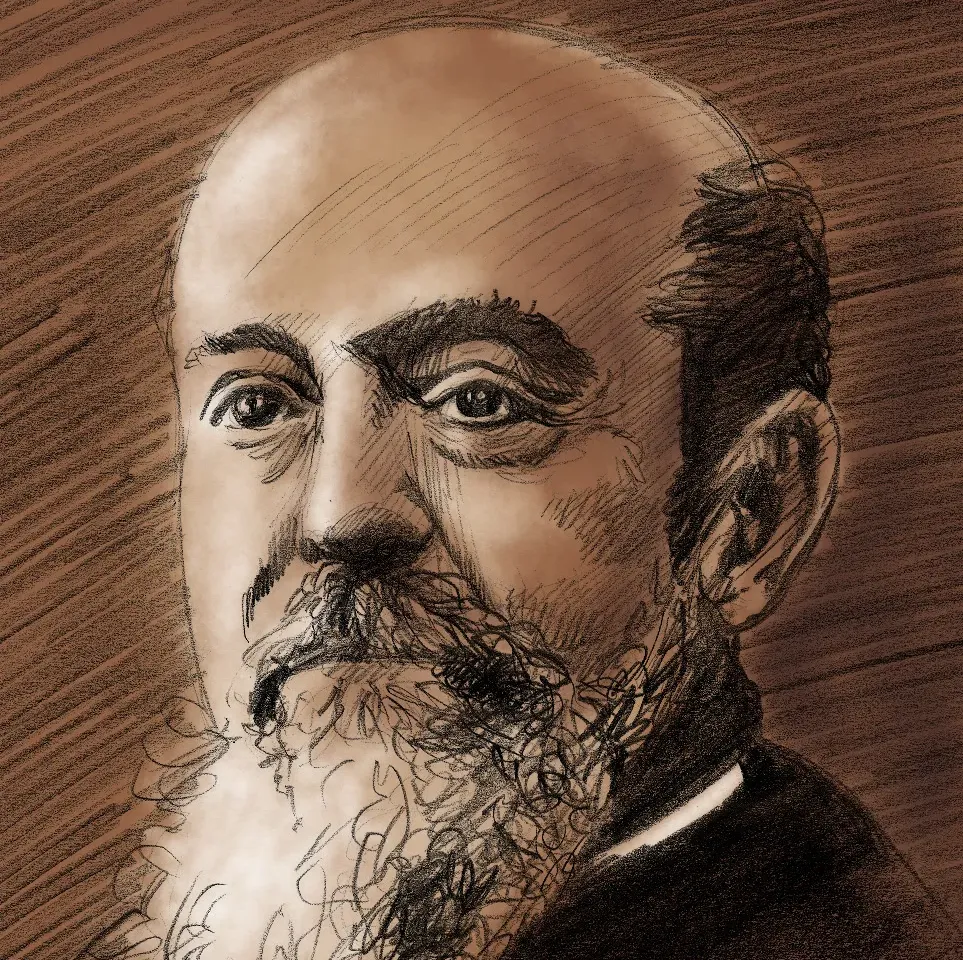

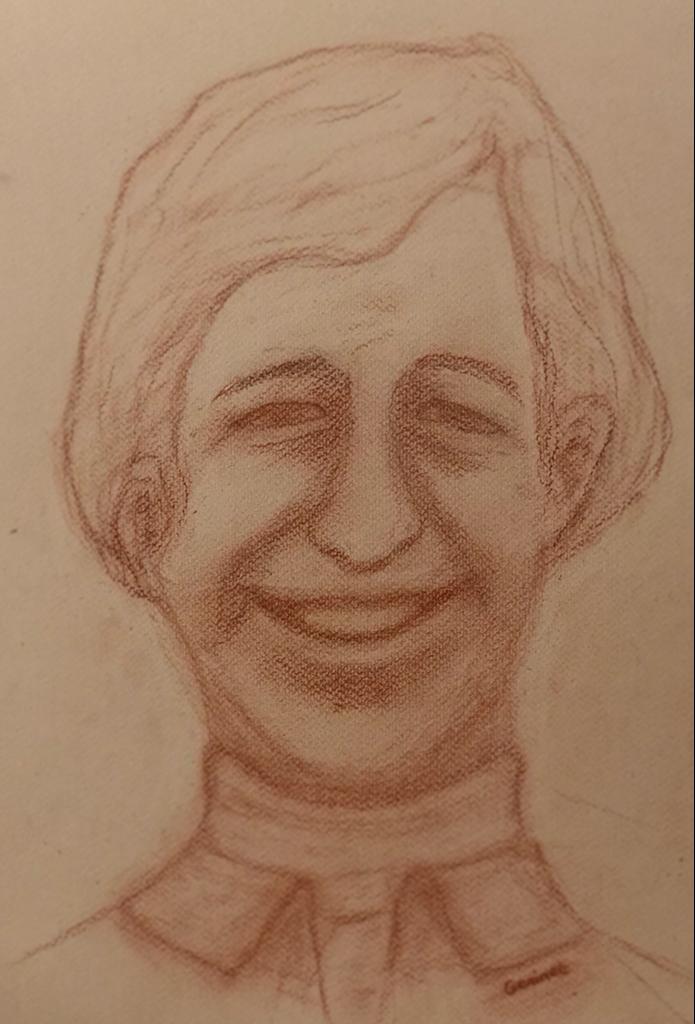

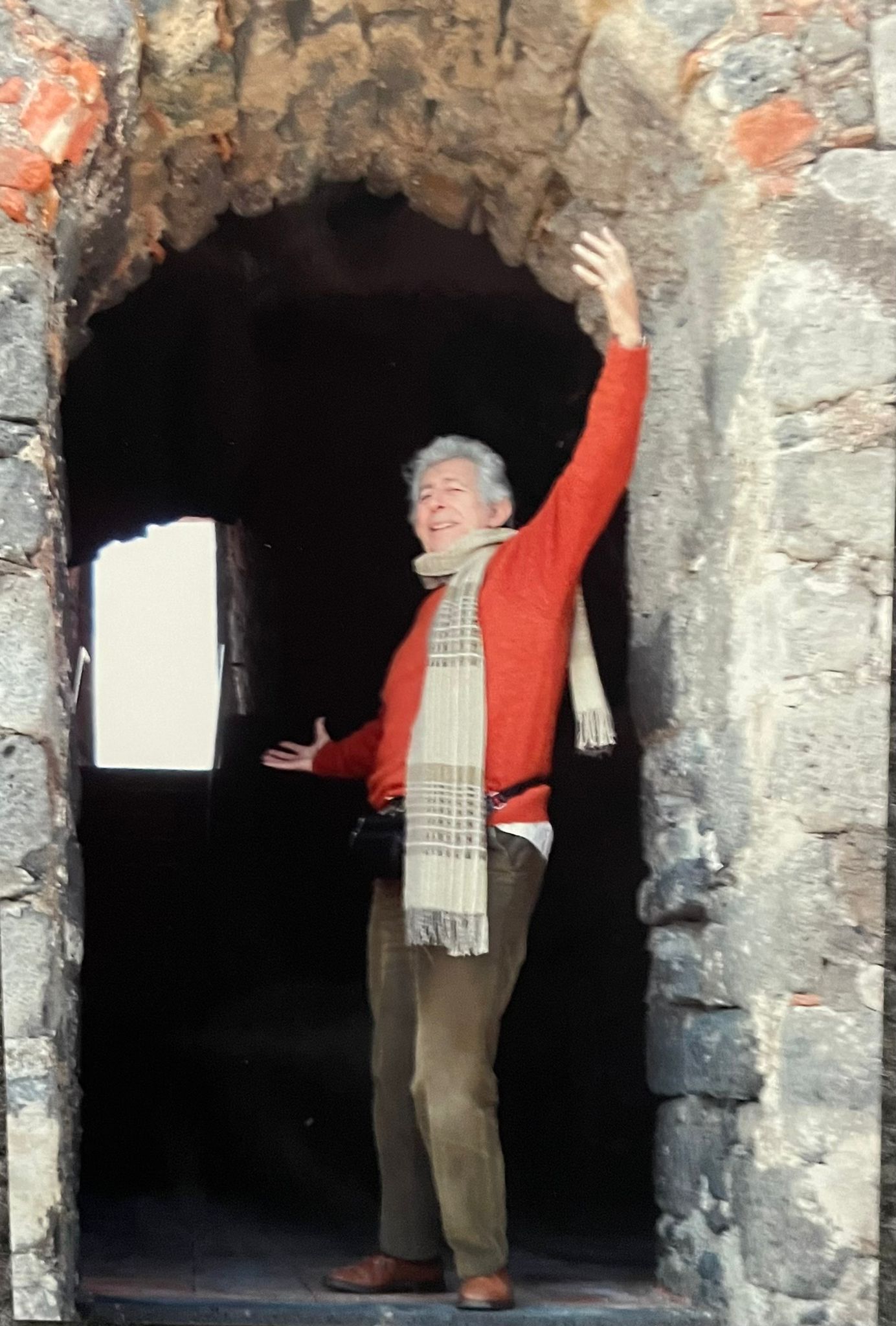

What vivid memories he left us, and what blessings they are. Erudite, insightful, kindly, generous, gracious, cosmopolitan, enthusiastic, humorous, caring, creative, cultured—somehow his expressive face and manner conveyed it all quite effortlessly. He was easy to like; he was easy to admire.

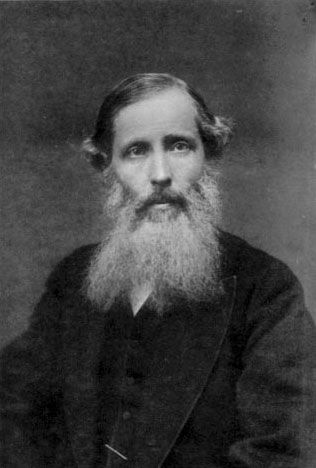

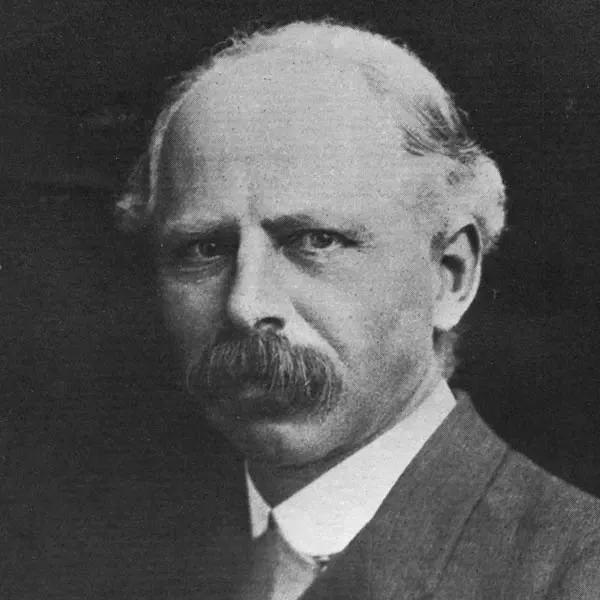

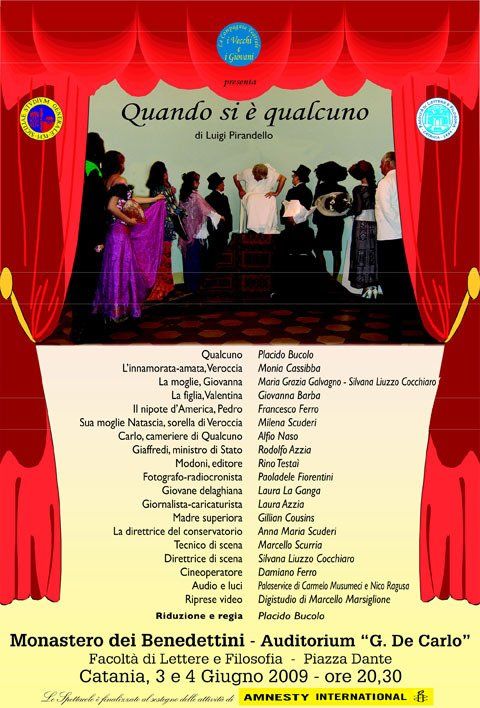

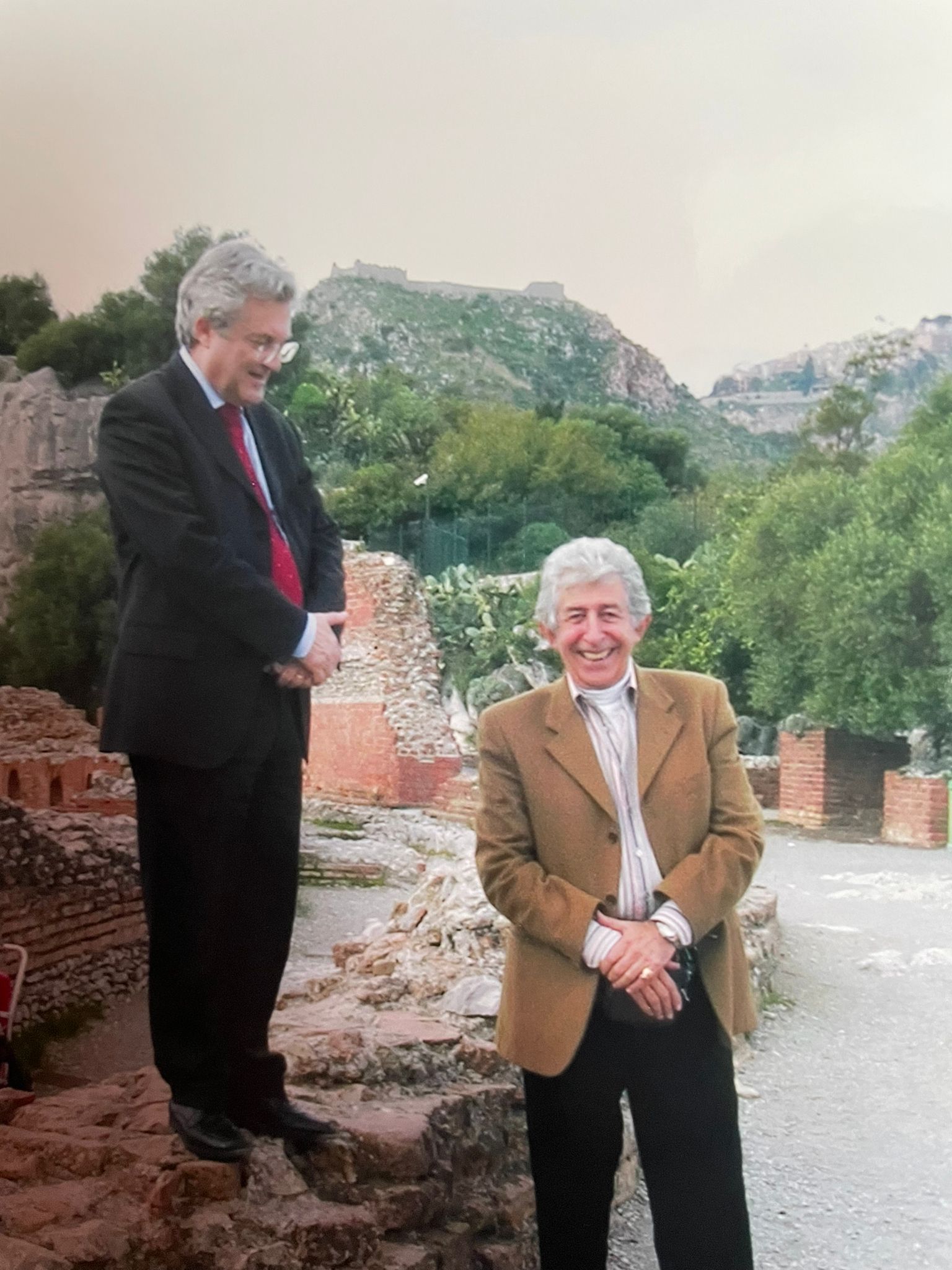

My direct personal contact with him helped reassure me that the large part of my life devoted to the study of the Victorian era philosopher Henry Sidgwick had not been wasted. Placido, following on his work on Pareto, had developed a passionate interest in Sidgwick and was engaged in a very serious effort to familiarize Italian academics with Sidgwick’s larger significance. Somehow, in part thanks to the intervention of senior Sidgwick scholar Jerry Schneewind, our long distance correspondence grew into a collaboration and an invitation to visit the University of Catania, at which Placido had orchestrated, as only a true maestro could, “Omaggio A Sidgwick”—the first of a series of international conferences (all with stellar casts) devoted expressly to the life and work of Sidgwick. Travelling to Catania with my wife and young daughter in November of 2006, I had little sense of the overwhelming experience that awaited us.

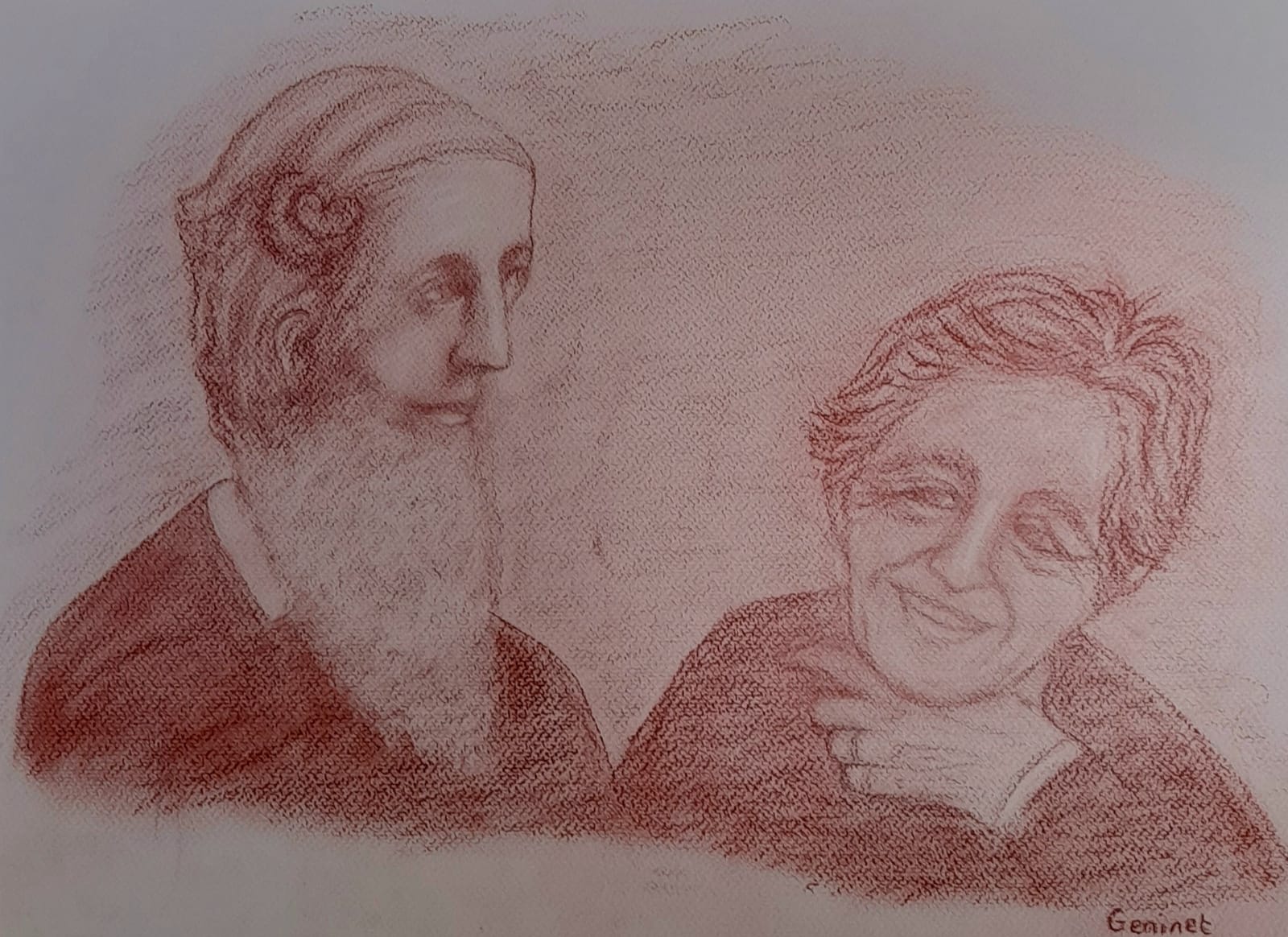

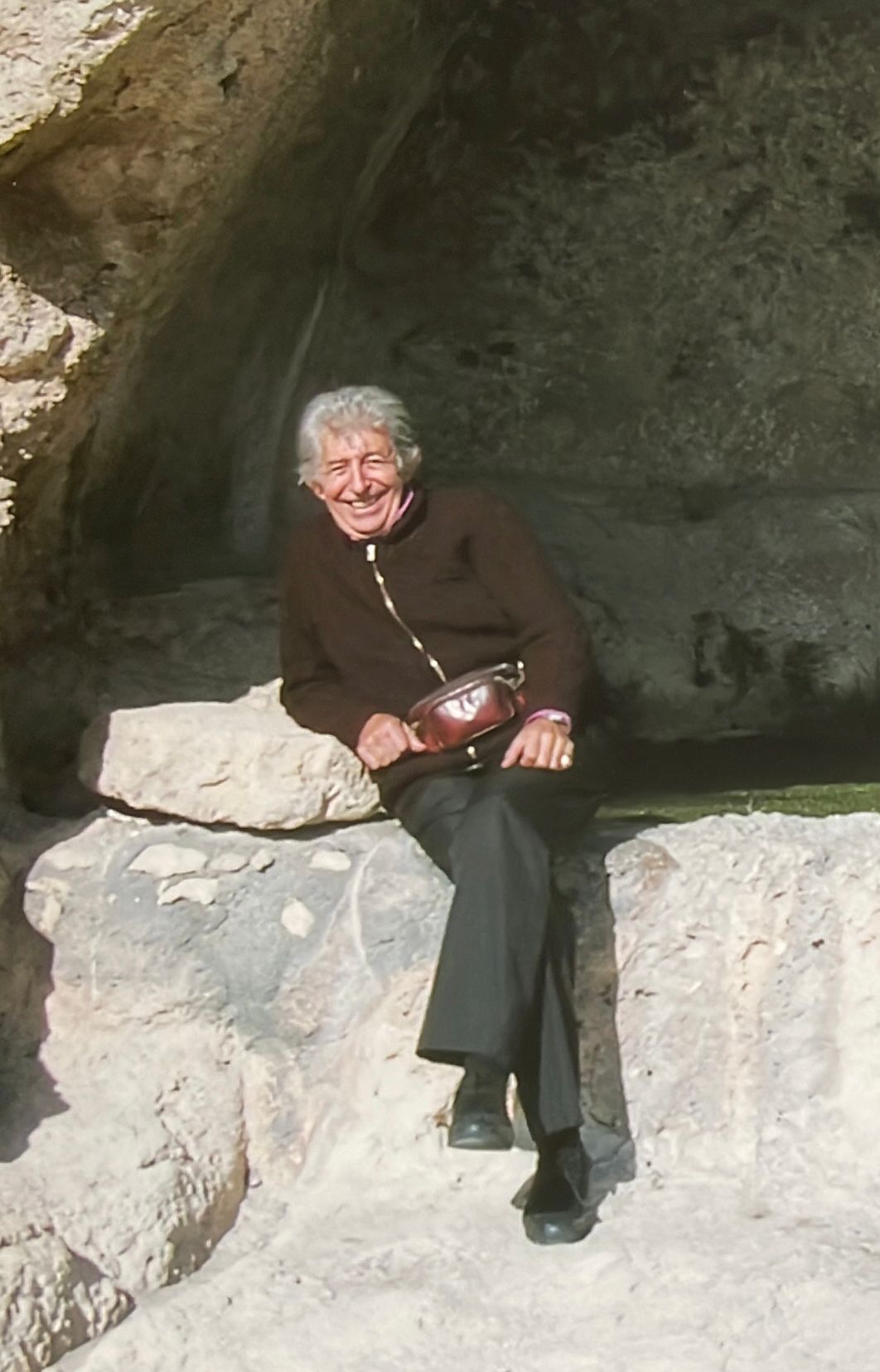

The conference was perfectly brilliant, as were its later iterations, and Placido was the brightest of stars. The volumes of conference proceedings speak for themselves. But the experience was profoundly amplified by Placido’s extraordinary hospitality and the time spent with him and Gillian, his equal in graciousness, at their home on the slopes of Mt. Etna. The warmth of the occasion, shared with the wonderful Roger Crisp who had come in from Oxford, set a new standard for what it means to host an academic conference. The thoughtfulness with which they handled everything, from accommodating my celiac condition to allowing my very young daughter to join us at a performance of Don Giovanni at the famous Catania Opera House—she was spellbound by it, to the astonishment of the adult company—was so deeply moving I can scarcely recall anything even vaguely comparable, in my academic life. Trips around Catania, to Syracuse, and to Taormina filled out the visit in such memorable ways. Driving back down the coast from Taormina to Catania at night, with rivers of lava flowing down the slopes of the erupting Mt. Etna off to the west, and Placido educating us from the driver’s seat, frames him in my memory forever.

On balance, he had the right approach to Sidgwick, and to life. He was open to and curious about all the dimensions of Sidgwick’s life and work, the arguments of The Methods of Ethics, to be sure, but also Sidgwick’s practical ethics, politics, and religious struggles, his spiritual quest, manifested in his lifelong devotion to parapsychological research. He was struck by the lines on p. 508 of Henry Sidgwick, A Memoir: “Well, I myself have taken service with Reason, and I have no intention of deserting. At the same time I do not think that loyalty to my standard requires me to feign a satisfaction in the service which I do not really feel. I am conscious of hankerings after Optimism, and if I yielded to these hankerings, I really think the haven of rest that I should seek would be the Church of Rome, just because of the insistence on authority ... There seem to me only two alternatives: either my own reason or some external authority; and if the latter, as my own reason would have to be exercised for the last time in choosing my authority, I should not hesitate to choose the Roman Church on broad historic grounds.” I had to relate to him that in one of my copies of this work, a copy that had been owned by Sidgwick’s

Cambridge student, friend, and colleague James Ward, there is an annotation in the margin by this passage with the single word “absurd,” a sentiment that many of Sidgwick’s academic philosophical admirers would probably endorse. Wrongly, it seems. This was a very mature, fifty-three year-old Sidgwick giving voice to what had really been a lifelong spiritual quest and frustration with the limits of reason. Yes, he wanted Reason to win. But he never thought that it had, and the depth of his thought about that failure and how to deal with it was part of what animated Placido’s interest in Sidgwick, to his lasting credit.